The digital divide — the unequal distribution of internet performance and access across socioeconomic and geographic lines — has long represented a deficit in opportunity for both low-income populations and those in rural communities. But in the days and weeks since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, as people around the world shifted to working and schooling from home, the issue and its inequities have been thrown into sharper focus.

This series examines the data behind several yet-unexplored facets of the digital divide, the people and places it impacts most greatly, and what can and should be done to close this persistent gap.

Part I: Internet performance and income

Just over a month since COVID-19 forced a near-global shift to working and schooling exclusively from home, the need to bridge the digital divide has become even more apparent and important. Many families now rely solely on their home connections to take meetings via video conference or help their children complete the day’s lessons, not to mention leverage telemedicine to safely visit the doctor. But for the poorest among us — those who once had the option to visit the local library or head into the office to get a reliable connection — the bandwidth available to them at home often isn’t enough.

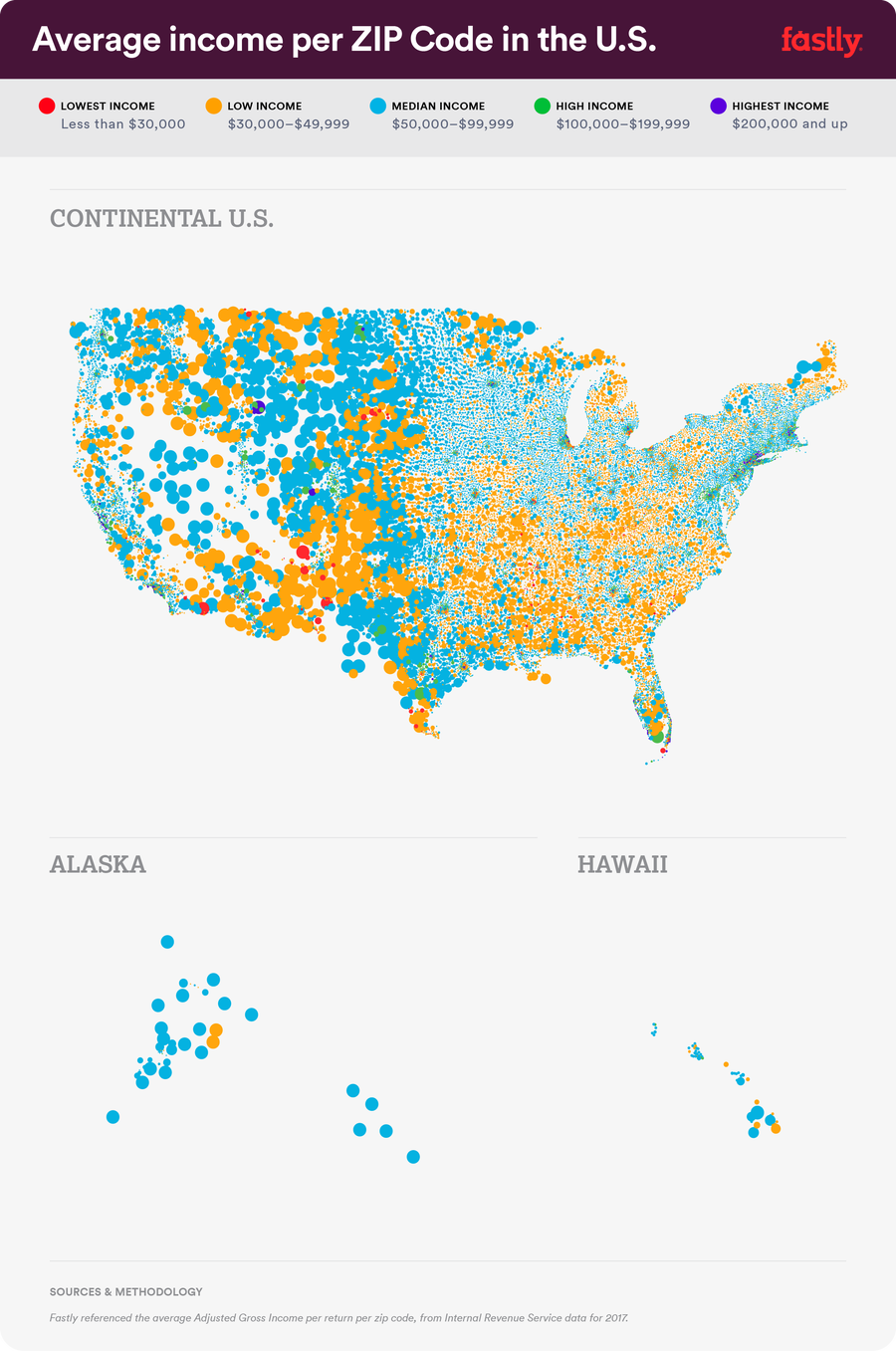

To understand the degree to which the digital divide is affecting low-income families during the COVID-19 pandemic, we compared download speed against five median income brackets in the U.S. using 2017 tax return data by ZIP Code from the Internal Revenue Service.

There are two important things to keep in mind as we dig into the data. First, download speed is a measure of bandwidth and internet performance that can be delivered per user in each household, and not necessarily the connection speed users are experiencing at home. And second, our data only represents those who have some sort of residential or mobile internet connection and does not include a group at the very heart of the digital divide issue — those without internet at all.

In our analysis, we discovered that the stratification of performance is even starker than we had hypothesized, that an acceptable connection is now more important than ever, and that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) have the power to make a significant difference.

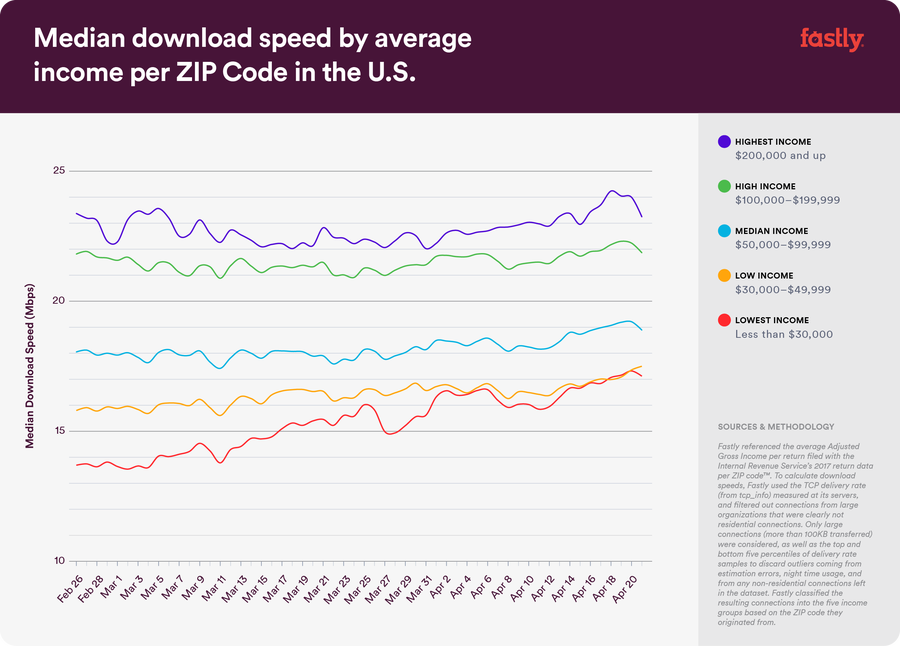

The parallel between internet performance and income is clear.

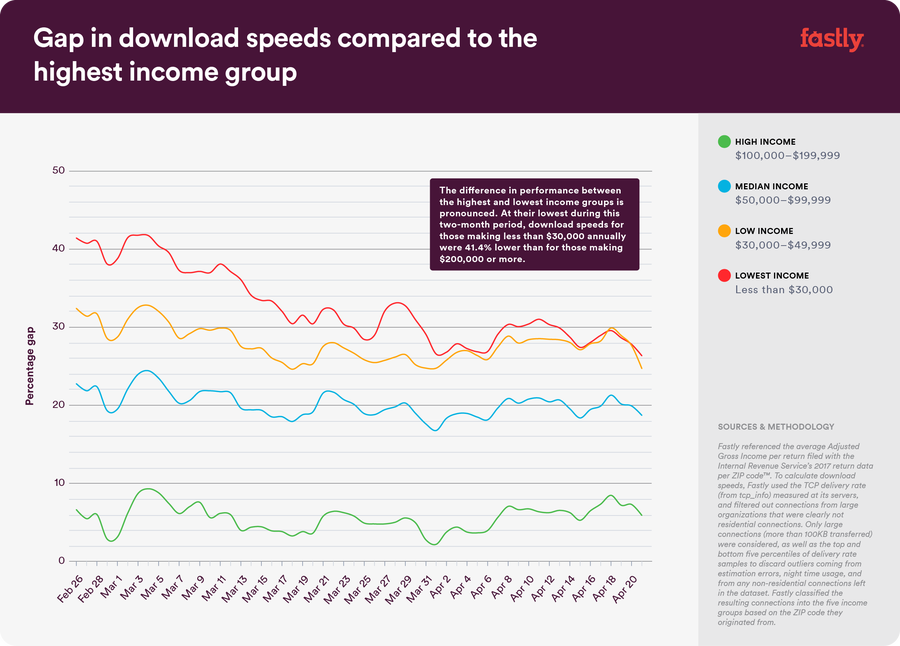

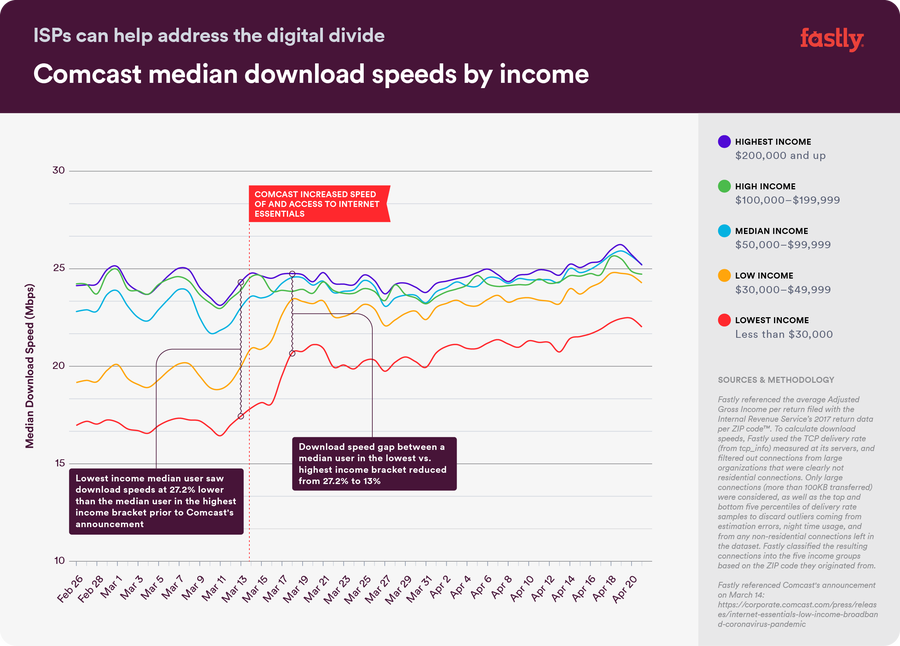

While digging into the data, we expected to see a noticeable difference in internet access and performance for low-income households. But what surprised us was how clearly and consistently the stratification aligns with income groups. As shown in the graph above, median download speeds track in decreasing succession from the highest income group to the lowest. The difference in performance between the highest and lowest income groups is pronounced: as you can see in the graph below, at their lowest during this two-month period, download speeds for those making less than $30,000 annually were 41.4% lower than for those making $200,000 or more.

Around mid-March, the red line representing download speeds for the lowest income neighborhoods begins to trend closer to the orange line representing download speeds for low-income neighborhoods. The downward trajectory here is actually a positive thing — it means that download speeds are increasing for that income bracket. Hold that thought; we’ll explain this hopeful finding shortly.

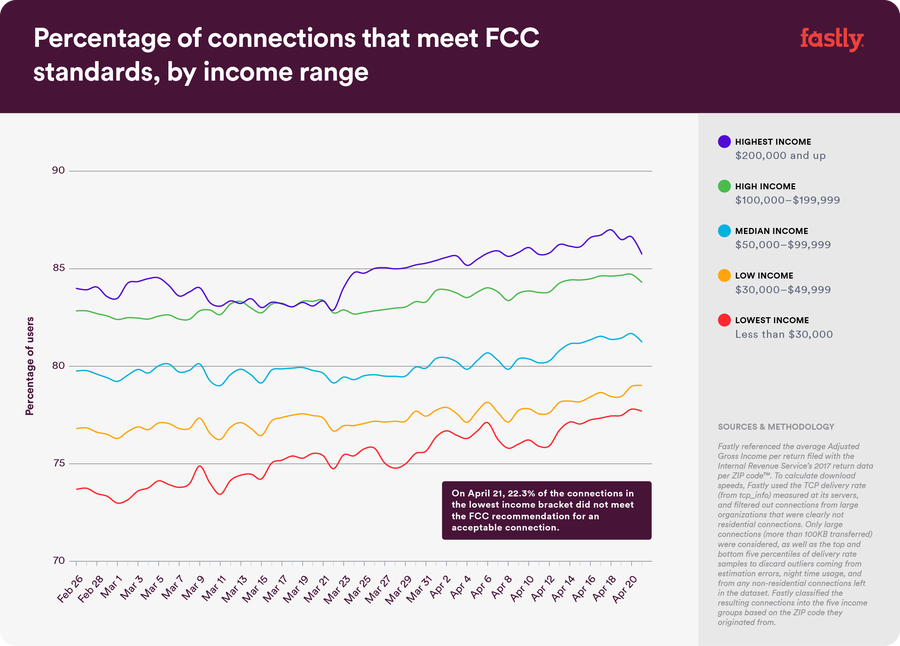

An acceptable connection is more important than ever.

The FCC recommends a minimum download speed of five Mbps for telecommuting and online learning. According to our data, on April 21, 22.3% of the connections in the lowest income bracket didn’t meet that recommendation, making working and learning from home amid the COVID-19 pandemic difficult, if not impossible.

ISPs can, and have, made a difference.

There is some good news to be shared from our research. Remember that visible lift in performance we mentioned? On March 14, Comcast announced a permanent increase in the speed of its Internet Essentials service (a package that is offered to all qualified low-income households for less than $10 a month) from 15 Mbps to 25 Mbps. In the graph below, you can see how this move significantly improved download speeds by 33% for the two lowest income groups, bringing them closer to parity with higher income brackets.

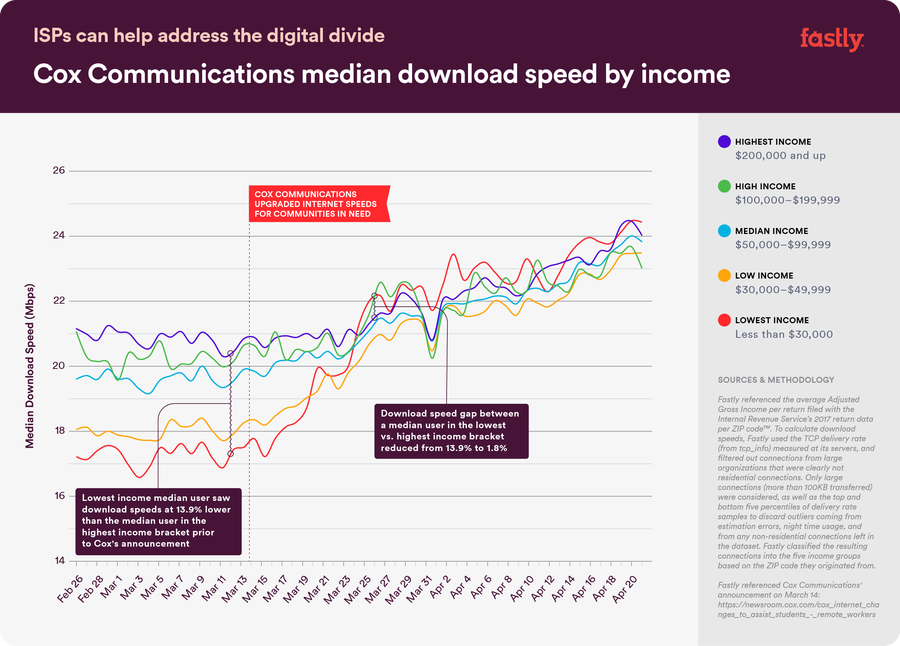

On the same day, Cox Communications made a similar announcement, upgrading its residential internet packages to 50 Mbps for 60 days. You can see that this had the most positive impact on the two lowest income groups, even causing their performance to surpass that of the highest income group at times.

What this tells us is that ISPs have the power and ability to close the digital divide in a meaningful way. Providing increased connectivity for low-income neighborhoods is a step in the right direction toward a more level digital playing field.

More equitable distribution is possible.

As so many are now required to work and learn from home, internet access and quality are, more than ever, a question of social justice. These factors now determine how effective an employee can be at their job, whether or not a student can learn the concepts necessary to progress to the next grade level, and how quickly someone can safely receive medical care. Thankfully, we can see that bridging the divide is possible. ISPs and mobile providers have the power to provide greater capacity and remove bandwidth restrictions and have done so amid this global health crisis. We are hopeful that others will follow suit, both now and in the future, as we head toward the new normal that awaits us on the other side of recovery.

Methodology and sources

Income data: We used public data from the IRS that allowed us to find the average Adjusted Gross Income per return filed with the IRS per ZIP Code for 2017. We then classified ZIP Codes into five annual income categories:

Lowest = less than $30,000

Low = $30,000–$49,999

Medium = $50,000–$99,999

High = $100,000–$199,999

Highest = $200,000 or more

Geo data: We used the Digital Envoy GeoIP database, and mapped the IPs to ZIP Codes using the US Census Bureau’s public ZIP Code dataset.

Download speeds: We used the TCP delivery rate (from tcp_info) measured at our servers, and filtered it as follows: We discarded connections from large organizations that were clearly not residential connections. We only considered large connections (more than 100KB transferred), and we dropped the top and bottom five percentiles of delivery_rate samples to discard outliers coming from estimation errors, nighttime usage, and from any non-residential connections left in the dataset. We classified the resulting connections into the five income groups based on the ZIP Code they originated from.